The use of morphing techniques to transform images. Click the images for larger versions and more information.

Composite portraits

"The Face of the Future?" Composite portrait

Click on image for an account of this project.

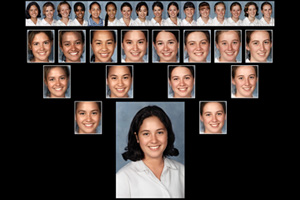

Digital composite portraits made using morphing software to produce an ‘averaged’ image from multiple source photographs. Click on the thumbnails for larger versions and more information.

The images show the source portraits at top, successive ‘generations’ below (the products of morphing each image-pair above them), and the final enlarged composite at bottom.

The notion of a composite photographic portrait is not new: in the late nineteenth century in England, the scientist Francis Galton pioneered a technique for making such composites (to illustrate human ‘types’ among other things) by successively copying registered portrait prints onto a single photographic plate. The exposure for each individual was determined by dividing the total exposure by the number of prints in the sample. Among his experiments were ‘averaged’ criminals, mixtures of family members, and composites of heads on ancient coins such as Alexander the Great, Nero and Cleopatra. If Galton had expected the composite of Cleopatra to reveal her legendary beauty he was to be disappointed; still, he wrote, it was "better" than any of the individual components, “none of which gave any indication of her reputed beauty; in fact, her features are not only plain, but to an ordinary English taste are simply hideous.”

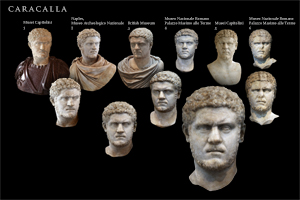

Below, some further examples using modern morphing techniques to produce composite portraits of ancient Roman historical figures.

|

Composite portrait of the emperor Nero |

Composite portrait of the empress Livia |

|

Composite portrait of the emperor Caracalla |

Composite portrait of the emperor Vespasian |

The compositing process increases the ‘signal-to-noise’ ratio by smoothing out the idiosyncracies and particularities of each source image. This inevitably tends to ‘beautify’ and, with art works such as paintings and sculptures, will increase any idealizing tendency already present. In the case of the Roman portrait busts and coin seen here, whether the average tends toward a truer likeness, while plausible, is of course moot in these instances.

Below is an animated example of the morphing process, using two portrait busts of the Roman emperor Vespasian.

Cat morph Click image for animation |

A smile |